Venus is moving from Capricorn to Aquarius in the next 24 hours.

#Venus #Aquarius #Capricorn

Venus is moving from Capricorn to Aquarius in the next 24 hours.

#Venus #Aquarius #Capricorn

Mars is moving from Capricorn to Aquarius in the next 24 hours.

#Mars #Aquarius #Capricorn

|

|

| The Moon and Earthshine, imaged 2018 January 20 from Alexandria, Virginia with an Explore Scientific AR102 10.2-cm (4-inch) f/6.5 refractor and a Canon EOS Rebel SL2 DSLR. |

The Moon returns to the evening sky this week, waxing through her crescent phases as she wends her way toward the bright constellations of winter. First Quarter occurs on the 10th at 5:45 am Eastern Standard Time. As Luna passes through her crescent phases look for the phenomenon known as “earthshine”, where the part of the Moon’s disc that’s not in direct sunlight glimmers with a pale bluish tint. This glow is actually a reflection of ourselves, caused by sunlight reflecting off our blue home planet and faintly illuminating the Moon’s “night” side. On the evening of the 8th look for the Pleiades star cluster a few degrees northwest of the Moon. Can you still discern the earthshine that night?

Most of us are familiar with the expression “March comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb”. This expression aptly describes the fluctuation of weather conditions in the northeastern U.S., where it can be cold and blustery one day and balmy the next. However, as with many such sayings, there is an astronomical connection as well. As evening twilight fades, the bright stars of winter still dominate the sky as the meridian splits the Great Winter Circle. However, quietly entering the sky in the east is the leader of the springtime constellations, the bright star Regulus. Unlike its winter companions, Regulus stands alone as the brighter stars initially command your attention, but as the night passes Regulus steadfastly climbs toward a place of prominence. Regulus, which translates from Latin origins as “Little King” is the brightest star in the constellation of Leo, the Lion, and for me is one of the sure signs of the coming spring. From suburban skies you may notice an arc of stars above Regulus that form a semicircle that outlines the regal head of the Lion. These stars form an asterism with Regulus known as the “The Sickle”, and, together with a right triangle of fainter stars to the east, outline a reasonable facsimile of a crouching beast. Leo is another ancient constellation, venerated by the ancient Egyptians as yet another embodiment of the Sun god and depicted as a lion on the famous astrological ceiling in the Temple of Denderah. Babylonian astronomers recorded the position of Regulus in 2100 BCE, and two millennia later the Greek astronomer Hipparchus used these observations to discover the 26,000-year cycle of precession of the equinoxes. In Greek mythology, Leo represented the Memaean Lion, slain by Hercules as one of his twelve labors.

Leo has a number of interesting sights for the owners of modest telescopes. While the bright winter constellations are rife with colorful stars, star clusters, and gaseous “nebulae”, the spring skies, led by Leo, offer views of distant external galaxies and colorful double stars. One of my favorite double stars lies about 8 degrees north of Regulus. Here you will find Leo’s second-brightest star Algieba, which shines with a slight yellow hue. Through a small telescope it resolves into a close pair of gold-tinted stars whose colors have a striking saturation. Under dark skies an 8-inch aperture telescope will reveal a small cluster of galaxies just two degrees north of Algieba. With a simple nudge of the telescope your view will expand from about 130 light-years for the star to 80 million light-years for the galaxies.

The bright planets are all gathering in the pre-dawn sky this week. Dazzling Venus and dimmer ruddy Mars continue to move in concert, both rising at around 4:30 am local time. They should be easy to spot by 6:00 am in the southeast.

Closer to the southeast horizon try to catch a glimpse of fleet Mercury and distant Saturn. You will ideally need an ocean horizon to get a good view, but a low, flat view to the southeast half an hour before sunrise should reveal the pair. Mercury will be just over half a degree south of Saturn and a bit brighter on the morning of the 2nd; use binoculars to try to spot the pair.

|

|

| Messier 42, the Great Nebula in Orion, imaged from Alexandria, Virginia, 2022 February 21 with an Explore Scientific AR102 10.2-cm (4-inch) f/6.5 refractor and a ZWO ASI183MC CMOS imager. |

The Moon retreats to the morning sky this week, waning from Last Quarter as she dives to the southernmost reaches of the ecliptic. New Moon occurs on March 2nd at 12:35 pm Eastern Standard Time. If you are up before the Sun you will have some interesting sight to see as morning twilight begins to brighten the sky. On the morning of the 24th you’ll find the Moon just three degrees northeast of the bright star Antares in Scorpius. On the 27th Luna, Venus, and ruddy Mars greet early risers with an attractive grouping in the southeastern sky.

The Moon’s absence from the evening sky means that it’s time for the February observing campaign for the Globe at Night citizen science program. The target constellation for February is Orion, which is high in the southern sky, crossing the meridian at 7:30 pm local time. Orion is the easiest constellation to view in the program, with his distinctive outline visible from just about anywhere, including the centers of light polluted cities. The basic idea of Globe at Night is to have people look at a patch of the night sky centered on a familiar constellation, then use the online star charts to determine the faintest stars that you can see from your location. Choose a clear night and try to view the sky from a location away from the direct glare of artificial light sources. Let your eyes adapt to the darkness for at least 10 minutes before you look at the sky. Report your observations on the Globe at Night web app. In 2021 over 25,000 observations were recorded from all 50 states and 90 countries around the world.

We have reached a time of year when we can observe two constellations on opposite sides of the sky that share both physical and mythological characteristics. We have already mentioned Orion in past editions of “The Sky This Week”. This constellation is known for its red supergiant star Betelgeuse and it bright, blue-tinted companion stars. These blue stars are part of what is known as an “O-B Association”, a physically bound group of very young, energetic stars of spectral types O and B that have a common origin. The site of their birth is the Great Nebula, which can be easily seen in binoculars as a small fuzzy patch in the asterism known as The Sword. Halfway around the sky, and now rising in the southeast before the beginning of morning twilight, is the red-tinted star Antares, the brightest star in the constellation of Scorpius, the Scorpion. It, too, is a red supergiant star, and it is surrounded by bright blue stars that form another O-B association. These physical similarities are remarkable in their own right, but the two constellations are also linked in the Greco-Roman mythology that defines our sky lore. According to these traditions, Orion was a half-mortal demi-god gifted with extraordinary hunting prowess. At one time he boasted that he could kill any animal on Earth. This claim angered Gaia, the Earth Goddess, who decided to teach the brash Orion a lesson. She sent a lowly scorpion to kill him, and almost succeeded. The scorpion stung Orion on his foot, and he came perilously close to death before being saved by Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer, identified by the Romans as the healer Asclepius. When Zeus placed the participants in the sky, he put them on opposite sides of the sky so they would never encounter each other again.

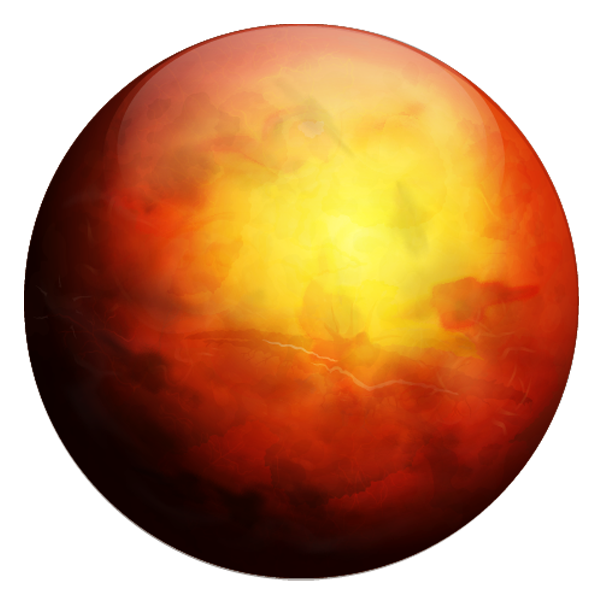

All of the bright planetary action now takes place in the pre-dawn sky. Venus is the most prominent object in the early morning hours, blazing away over the southeastern horizon. She rises at around 4:15 am local time and is easily seen as morning twilight gathers.

Just to the south of Venus is ruddy Mars. While Venus dazzles, Mars is much more subdued. He is best identified by his pale reddish hue. He seems to track Venus as both planets move eastward against the stars, and over the course of the week they inch closer together. Get up early on the morning of the 27th to see a beautiful grouping of Venus, Mars, and the waning crescent Moon.

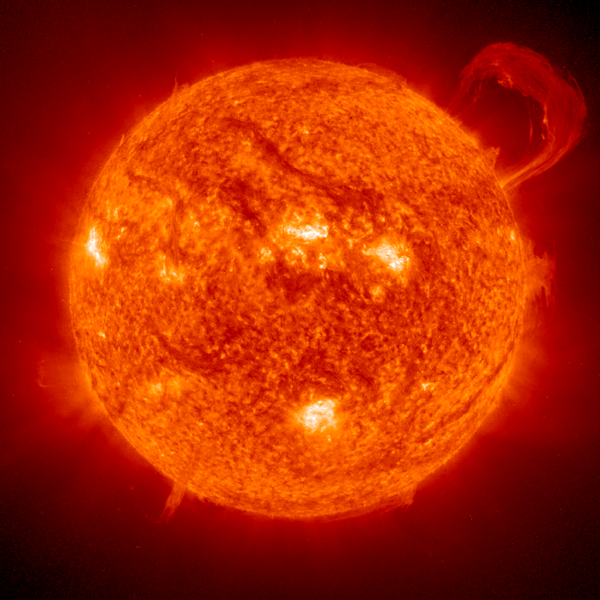

The Sun is moving from Aquarius to Pisces in the next 24 hours.

#Sun #Pisces #Aquarius

|

|

| The Big Dipper standing on its "handle", imaged 2019 February 16 from Mollusk, Virginia with a Canon EOS Rebel SL2 DSLR. |

The Moon begins the week beaming down from her perch among the stars of Leo, the Lion. She wanes from her full phase to Last Quarter, which occurs on the 23rd at 5:32 pm Eastern Standard Time. As Luna’s phase wanes she dives southward along the ecliptic, passing through the rising constellations of spring.

The Full Moon washes out all but the brightest stars as the week begins. Fortunately, the early evening hours are dominated by the bright stars and constellations of the Great Winter Circle. Orion and his bright, colorful cohorts cross the meridian at 8:00pm. No matter how bright the sky appears, the stars of this region provide a splendid start to an evening’s stargazing. Orion’s distinctive shape and his placement straddling the celestial equator have made him the most recognized constellation we see in the sky. He is visible from every inhabited part of the Earth, and his outline figures prominently in the sky lore of virtually every culture that has turned its collective gaze skyward. To the ancient Egyptians he represented Sahu, the immortal soul of Osiris, god of the Underworld. A wonderful depiction of Sahu, followed by the star Sothis (which we now call Sirius) may be found in the famous “Zodiac of Denderah” that once graced the walls of the temple of the goddess Hathor at that site. The temple is some 2500 years old, but it is based on sky lore that pre-dates the temple by 2000 years, where we find descriptions of Sahu linked with the souls of deceased pharaohs from Egypt’s earliest dynasties.

Orion’s stars shine with an icy blue tint with the exception of Betelgeuse, which marks Orion’s shoulder. A casual glance will show a distinctive reddish tint to Betelgeuse, which we now know indicates a relatively cool surface temperature compared to its cohorts. Betelgeuse is the brightest of a class of stars known as red supergiant stars, which are highly evolved and nearing the end of their lifetimes. Most of the other stars in Orion are blue supergiants, which are comparatively young in their evolution. These stars are highly luminous, shining with the equivalent energy of many thousands of Suns, and for the most part they are thousands of light-years away. Orion’s stars seem to have originated in the Great Orion Nebula, which is one of the largest star-forming regions in our galaxy.

While Orion dominates the early evening hours, another familiar star pattern begins to become prominent in the northeastern part of the sky. The asterism that we call the “Big Dipper” seems to stand on its “handle” as the night progresses, and when I see it I’m assured that spring is not too far in the future. Although it doesn’t sport the blazing stars of Orion, the seven stars that make up the Dipper asterism still form a shape that is instantly recognized by residents of the Northern Hemisphere. Like Orion, the Dipper is associated with the sky lore of many ancient peoples. It was a central focus of many Native American cultures which used its annual excursions around the north celestial pole as a calendar to time their agricultural activities. In the Greco-Roman skylore that forms the basis of our constellations the Dipper formed part of the larger constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. Interestingly, it also represented a bear to some indigenous North American cultures.

This will most likely be the last week that we will see Jupiter in the evening sky until late June. The giant planet now wallows in twilight and sets within an hour of sunset as the week begins. By next week Old Jove sets a bit more than half an hour after the Sun.

Venus is now very prominent in the pre-dawn sky, rising in the southeast at around 4:30 am. By 6:00 she is well above the tree line and can be easily picked out in the gathering twilight.

Mars accompanies Venus in the morning twilight, but he is pale by comparison to his dazzling neighbor. You will probably need binoculars if you try to find him in the brightening twilight, but he shouldn’t be too hard to see just south of his blazing companion.

Mercury is moving from Capricorn to Aquarius in the next 24 hours.

#Mercury #Aquarius #Capricorn

|

|

| The Moon, imaged 2021 April 20, 01:31 UT from Alexandria, Virginia with an Explore Scientific AR102 10.2-cm (4-inch) f/6.5 refractor, Antares 1.6X Barlow lens, and a ZWO ASI224MC CCD imager. |

The Moon waxes as she arcs through the stars of the Great Winter Circle this week. Full Moon occurs on the 16th at 11:56 am Eastern Standard Time. February’s Full Moon is popularly known as the Snow Moon, since February is typically the snowiest month of boreal winters. Abundant snow and cold temperatures also impact provisions stored for the season, so another name is the Hunger Moon. On the evening of the 9th you will find the Moon between the ruddy star Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster; on the 13th she passes close to Pollux, the brighter star of the Gemini twins.

Although February is the year’s shortest month, it is the one when most of us really begin to notice the increasing length of daylight. This week the length of day is one hour longer than it was back on the winter solstice, and we tack on nearly another hour by the month’s end. On average each day is about two and a half minutes longer than its predecessor, and this rate will be maintained through the upcoming equinox in March. If you enjoy early evening stargazing, take advantage of the next few weeks. The switch to Daylight Time will happen on March 13.

This is a great week to take long, leisurely looks at our only natural satellite, the Moon. I often say the Luna is “looked over, then overlooked” by neophyte astronomers. It is often the first target that new telescope owners look at, but often that first look is rarely followed up. The Moon’s surface is frozen in geological time; it has hardly changed over the course of the last billion years. However, these features offer a testament to the violent beginnings of the solar system itself. The large, seemingly flat features dubbed “seas” by early telescopic observers are the remnants of colossal collisions with planet-sized objects that abounded in the formative days of our planetary system. These collisions allowed molten rock from the proto-Moon’s interior to flood large areas of its surface. The brighter “highland” terrain provides a record of the ferocity of this early bombardment as countless smaller “planetessimals” pockmarked the surface shoulder-to-shoulder. As the terminator line slowly moves across the Moon’s face these features are gradually revealed, and it is always interesting to examine them as the lighting conditions change. What I enjoy in my evenings with the Moon is the sheer number of these ancient scars of violent formation, and the uniqueness of each one.

As the Moon brightens, though, she washes out the fainter stars of the night sky. Fortunately, about one third of the brightest stars in the night occupy this part of the sky, so the Moon won’t be the only thing to attract your attention. As much as I enjoy looking at the Moon through my smaller telescope, sweeping past all of the bright stars of the Great Winter Circle is also a rewarding experience. Starting with the bright stars of Orion, then moving around the circle counter-clockwise, each star shines like a brilliant gemstone. Betelgeuse and Aldebaran remind me of garnets, Capella is a blazing point of amber, while Rigel and Sirius are dazzling sapphires.

Jupiter can still be seen shortly after sunset in the southwest, but he beats a hasty retreat before the end of evening twilight, setting at around 7:00 pm. He will disappear by the end of the month, passing behind the Sun in early March.

Venus has seemingly vaulted into the morning sky. After the recent string of cloudy days I was surprised by her glowing presence in the southeast when I arose at 6:00 am. She will linger in this area of the sky for the next few weeks, drifting eastward against the dim autumnal constellations.

You will find ruddy Mars several degrees below Venus’ bright glow. The two planets will move in tandem for the rest of the week, gradually edging closer together. They will remain a “duo” through most of March.

|

| Crescent Moon, imaged 2016 December 30 from Mollusk, Virginia with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i DSLR. |

The Moon waxes in the evening sky this week, coursing her way northward along the ecliptic toward the bright stars of the Great Winter Circle. First Quarter occurs on the 8th at 8:50 am Eastern Standard Time. Look for the slender lunar crescent a few degrees south of Jupiter in the evening twilight glow on the evening of the 2nd. Luna ends the week approaching the Pleiades star cluster and the bright star Aldebaran in the constellation of Taurus, the Bull.

February 2nd is one of those odd “non-holidays” that is widely observed throughout the U.S. Popularly known as Groundhog Day, its origins lie in ancient astronomical folklore that was prevalent throughout many European cultures in medieval times. We all know that there are four astronomical seasons that anchor the calendar. However, each season also had a mid-point known as a “cross quarter” day. These dates became the traditional dates for serfs to pay rent on their land to their feudal masters. They were also important feast days observed by pagan religions and were especially important to Celtic and Germanic cultures. As Christianity swept the old religions aside, the cross-quarter days were tied to Christian feasts and festivals that have endured to the present day. Our Groundhog Day was known as Imbolc to the Celts, who celebrated a feast to the pagan goddess Brigid on February 1st. The Christian tradition celebrated “Candlemas” on February 2nd, commemorating the presentation of the infant Jesus at the Temple for his purification ritual. So how did a religious feast day become defined by the prognostication prowess of a hibernating rodent? That tradition comes from Germanic observances in which weather lore met religious celebration. In these traditions the emergence of hibernating animals under clear or cloudy skies served as a predictor for the arrival of spring-like weather. Originally bears were the animal of choice, but as their numbers dwindled in northern Europe the badger became the chosen messenger. When German-speaking people emigrated to America in the 18th and 19th Centuries they brought their tradition with them and settled in southeastern Pennsylvania, where badgers were scarce but groundhogs were plentiful. The town of Punxsutawney began the annual observance of Groundhog Day in 1886, and they’ve been doing it ever since.

How “precise” is the large rodent’s annual prognostications? The legend says that if he sees his shadow, we’ll have six more weeks of winter. 46 days will elapse between Groundhog Day and the vernal equinox on March 20th. Simple math tells us that a tad more than six weeks fill that span, so he’s not too far off base. However, the lengths of the seasons slowly change with time due to precession of the Earth’s poles, so the actual cross-quarter day actually occurs on February 4th. Using this starting point the equinox occurs in six weeks and two days. Six weeks seems reasonable to me. Unless it’s cloudy on Groundhog Day!

As we’ve already mentioned, cross-quarter days mark the mid-points of the seasons, and we still observe most of them. Groundhog Day and Halloween are the most widely observed here in the U.S., and May Day is still widely observed in Europe. Lammas, the August Cross-quarter day, is no longer widely celebrated, but for many of us August 1st is the traditional stars of our summer vacations. Perhaps Lammas still lingers?

Jupiter still lingers in the evening twilight, but his days are numbered. By the end of the week he sets at the end of evening astronomical twilight, and by this time next month he will be hidden behind the Sun. He gets one last fling with the slender crescent Moon on the evening of the 2nd. He will next grace our evening skies in the middle of the upcoming summer.

You will find ruddy Mars below the bright dazzle of Venus during morning twilight. The two objects appear low in the southeastern sky with Mars some 10 degrees southwest of Venus as the week begins. By the week’s end Mars will be about 7 degrees south of his much more brilliant companion.

|

|

| Messier 35 and NGC 2158, imaged 2022 February 22 from Alexandria, Virginia with an Explore Scientific AR102 10.2-cm (4-inch) f/6.5 refractor and a Canon EOS Rebel SL2 DSLR camera. |

The Moon spends the week waning in the morning sky, passing through the stars of late spring and early summer as she dwindles through her crescent phases. New Moon occurs on February 1st at 12:46 am Eastern Standard Time. Look for the Moon just north of the star Dschubba in the “head” of Scorpius before dawn on the 27th. Luna’s slender crescent will be just three degrees southwest of ruddy Mars in the brightening twilight of the morning of the 29th.

The January campaign for the Globe at Night citizen-science program runs for the duration of the week, and hardy stargazers can test their winter endurance by looking at the stars of Orion. This is probably the easiest of the campaign’s constellations to look at, since the Hunter’s distinctive shape is visible from every inhabited part of the globe and can be seen even from the heart of major metropolitan areas. The idea behind the program is quite simple; find Orion in the sky, then compare the number of stars that you can see with charts on the project’s web page. The Globe at Night project is an internationally recognized program that grew out of the 2009 observance of the International Year of Astronomy. From these humble beginnings it has grown a world-wide audience of observers, collecting over 25,000 observations during 2021. The data collected from these monthly campaigns helps astronomers and climate scientists assess the amount of artificial light that’s being directed up into the night sky and helps promote awareness of light pollution and its implications for the environment. The more people we can sensitize to the issue, the more likely we are to find a solution.

We often talk about the brilliance of the summertime Milky Way, but the faint band of the Galaxy’s glow is also a fixture of the winter sky. In the summer months we are looking across vast star clouds toward the Galaxy’s center, but during winter we are looking through less dense star clouds toward the Galaxy’s edge. Our solar system is located much closer to the edge than the center, so the Milky Way’s density is much less in the winter sky. Nonetheless, under crisp winter skies at dark locations the winter Milky Ways is still impressive. This is one of my favorite parts of the sky to explore with binoculars or small telescopes. Scan the sky between Cassiopeia in the northwest to the bright star Sirius in the southeast and you will notice dozens of knots of light, most of which are star clusters. The Pleiades in Taurus is one of the closest of these clusters, providing pleasing views for the unaided eye and a treat for binocular observers. High overhead in the constellation of Auriga, the Charioteer, binoculars will reveal several star clusters between the bright stars Capella and El Nath, the latter “shared” with Taurus. These clusters are best viewed in relatively small, low-magnification telescopes that allow you to “sweep” through the Milky Way’s stars. One of my favorite clusters is located among the stars that mark the “foot” of Castor, one of the Gemini twins. Messier 35 is easily seen in binoculars as a misty patch of light that resolves into hundreds of stars in a small telescope. That telescope will also reveal a faint smudge of light just west of the cluster. A larger telescope will resolve this glow into another, more remote cluster, NGC 2158. Dozens of these cosmic “jewel boxes” may be found as you sweep the sky just east of Orion through the faint stars of the constellation of Monoceros, the Unicorn down to the sky’s brightest star, Sirius.

You can still catch Jupiter in the evening twilight sky, but each passing night brings him inexorably closer to the Sun. By the end of evening twilight he hangs low in the southwestern sky, and by 7:30 pm he’s setting. Once he’s gone there are no bright planets to be seen until just before sunrise.

Mars rises at around 5:00 am local time, and he should be visible low in the southeast an hour later. He receives a visit from the waning crescent Moon on the morning of the 29th.

Bright Venus should also be visible in the brightening glow of morning twilight. You will find her to the east of Mars and the crescent Moon on the 29th.

Mercury is moving from Aquarius to Capricorn in the next 24 hours.

#Mercury #Capricorn #Aquarius

Mars is moving from Sagittarius to Capricorn in the next 24 hours.

#Mars #Capricorn #Sagittarius

The Sun is moving from Capricorn to Aquarius in the next 24 hours.

#Sun #Aquarius #Capricorn

|

|

| Orion and Sirius, imaged 2014 March 27 from Paris, Virginia with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i DSLR camera. |

The Moon wanes as she moves into the morning sky and the rising springtime constellations. Last Quarter occurs on the 25th at 9:41 am Eastern Standard Time. Late-night skywatchers can see Luna approach the bright star Regulus, the heart of Leo, the Lion, after she rises on the evening of the 19th. Early risers on the morning of the 24th can spot the Moon just north of the bright star Spica in the constellation of Virgo.

Stargazing at this time of year takes a certain amount of fortitude. The blasts of arctic air that pour down from the north can make an evening under the stars a test any person’s mettle. However, the cold air usually means low humidity and no haze, so we often experience nights with the highest sky transparency. I have found that crisp cold winter nights allow me to see stars that are about a magnitude fainter than those I can see in summer nights. The trade-off is that I have to bundle up from head to toe to enjoy a modicum of comfort. Fortunately we have modern materials to insulate us, unlike astronomers from the “classical” era of visual observing. One of America’s leading astronomers of the day, Edward Emerson Barnard, worked at the Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, spending countless winter nights observing with the great 40-inch refractor located there. He habitually observed in sub-zero conditions, much to the dismay and discomfort of his night assistants. A reporter once asked him how astronomers kept warm on long January observing sessions; his answer was “We don’t.”

The bright stars of the boreal winter sky offer little respite from the cold, but their cheerful glow and varied colors make cold weather observing a bit more tolerable. Foremost among these bright luminaries is Sirius, which trails the distinctive constellation Orion across the sky. Sirius is the brightest star in the sky, and, as such, has been deeply embedded in human culture since ancient times. The ancient Egyptians identified the star as Sepet, the soul of the goddess Isis, one of the oldest deities in their pantheon. The annual rising of Sirius just before the Sun preceded the annual flooding of the Nile, which sustained their civilization for 3000 years. Although it is often referred to as the “Dog Star” from its association with the constellation Canis Major, the star’s name derives from the ancient Greek word that means “the scorcher”. Indeed, when the star is near the horizon, atmospheric refraction causes the star to flicker through the colors of the rainbow, giving the impression of a dancing flame. Sirius owes its brightness to its proximity to the solar system at a distance of just 8.7 light-years. The star is about 23 times as luminous as the Sun and glows with a distinctive blue tint. Sirius was one of the first stars to have its motion across the sky measured. Edmond Halley (of comet fame) discovered its changing position in 1718 by comparing his measurements of the star’s position with those of Ptolemy and Hipparchus. In the decade between 1834 to 1844 the German astronomer Friederich Bessel noticed irregularities in the star’s proper motion and attributed them to an unseen companion circling the bright star. The companion, now known as Sirius B or “The Pup”, was discovered on January 31, 1862 by the American telescope maker Alvan Graham Clark while testing an 18.5-inch lens ground and polished by his father. It was the first white dwarf star to be discovered.

The only bright planet now easily visible in the evening sky is Jupiter, which pops out of the twilight glow in the southwestern sky about 15 to 20 minutes after sunset. Old Jove only spends an hour in the sky after evening twilight ends, and his proximity to the horizon makes it difficult to see fine details in his turbulent clouds.

You might be able to glimpse Saturn as twilight deepens, but the ringed planet now sets before the end of twilight. He is now far too low to observe with a telescope, but you should be able to spot him in binoculars.

Ruddy Mars may be glimpsed in the pre-dawn sky, low in the southeast, but you will likely need binoculars to see him. Half an hour before sunrise, look to the southeast for the bright glow of Venus if you have a low horizon. The dazzling planet will become much more prominent as the month ends.